Japan and the Armenian Genocide

A Forgotten International Humanitarian Relief Episode

The devastation and immense human suffering caused by the recent earthquake in Haiti resulted in an enormous international humanitarian relief response. Japan once again found itself participating in a global relief effort in a bid to save victims of a major disaster. More than $70 million dollars in aid for Haiti has been pledged by the Japanese government, including ¥30 million (or ~$357,000) in emergency supplies. This comes on the back of substantial contributions made by Japan to other recent natural disasters, such as the 2004 Great Asian Tsunami and the 2006 Indonesian earthquake.

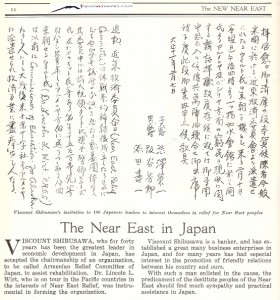

From the April 1922 issue of New Near East, p. 12.

According to Makiko Watanabe, formerly of the Japan International Cooperation Agency, Japan’s humanitarian assistance dates back to 1953, when the government started funding UN relief work for Palestinian refugees. Later in the 1970’s, Japan dispatched a small medical team to help Cambodian refugees. In 1987, this ad hoc help was formalized with the adoption of the Japan Disaster Relief Team Law (JDR Law) which officially enshrined the commitment by Japan to international relief.

The early history of Japan’s international humanitarian relief involvement has not been the subject of any major study. Consequently, Japan’s participation in global humanitarian relief before 1953 is little known, and has failed to gain adequate recognition in the context of Japanese philanthropic history.

Japan’s first-known involvement in international humanitarian relief was not in 1953, but in 1922—in response to the Armenian Genocide committed by the Ottoman state.

The global response to the genocide was sparked by a cablegram sent by the United States Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Henry Morgenthau, to the Secretary of State in Washington on Sept. 6, 1915, stating: “Destruction of the Armenian Race is progressing rapidly.” Morgenthau proposed the formation of a relief fund in the United States in order to “provide means to save some of the Armenians” who had survived. Within a few weeks a group of civic, business, and religious leaders formed a committee to rescue over a million people caught up in the tragedy.

The relief fund committee was eventually incorporated by an Act of Congress in August 1919 and called the Near East Relief (NER). By 1929, the organization had raised over $110 million (about $1.4 billion in today’s terms) and saved more than half a million Armenians from certain death. This figure included over 130,000 children who were housed, fed, and educated in more than 200 orphanages across the region. It was an unsurpassed achievement, remarkable even by today’s standards, accomplished through the pioneering of philanthropic techniques which continue to be used today.

In an effort to internationalize the NER, the Rev. Dr. Lincoln L. Wirt, an American Congregational minister and a Red Cross commissioner during World War I, was given the mission to establish branches of the NER among the Pacific nations. Wirt embarked upon his mission from San Francisco aboard the Golden Gate on Jan. 14, 1922. After successfully establishing a relief committee in Hawaii, he arrived in Japan in February, lodging at the Imperial Hotel Tokyo.

There were quite a number of Americans and Europeans in Japan at the time and it was to this community that Wirt addressed his appeal. He succeeded in forming a general committee, composed of American businessmen and missionaries, with the American Ambassador, Charles Beecher Warren, as chairman. The Armenian relief movement began to gain momentum and at foreign social groups, lodges, clubs, churches, and garden parties, Wirt was invited to speak.

While Wirt’s mission was successfully progressing, word was received through the Rev. Gilbert Bowles, a long-time American missionary in Japan, that a group of leading Japanese men were interested to learn about Wirt’s mission. Bowles was held in high esteem by the Japanese, and no foreigner had a better command of the Japanese language. Under the guidance of Bowles, Wirt was taken to the Imperial Bank and ushered to the director’s room. Acting as an interpreter, Bowles introduced Wirt to a number of personages including Viscount Shibusawa, a leading banker and vice-minister for foreign affairs. Sitting at the head of a long table, Shibuwasa asked Wirt “who the Armenians were and why they needed help.” After a little geography and history, Wirt described the details of the atrocities committed against the Armenians and their current plight. Shibusawa interrupted and asked, “Why did you not come to us with your appeal?” He added, “Was it because we are Buddhists and you thought we would not help Christians in distress? We have read your speeches as reported in the Japan Advertiser [an English-language daily] and we thought we would like to help, even if we have not been invited to do so. Unknown to you, one of our Japanese papers published your appeal, and here is your result.” Shibusawa handed over to Wirt a check for $11,000 (about $140,000 in today’s terms).

Viscount Eiichi Shibusawa

Shibusawa accepted the chairmanship of the newly formed Armenian Relief Committee of Japan, which was headquartered at 1 Uchiyamashita Cho, Kajimachi, Tokyo. The Rev. Gilbert Bowles was designated as secretary of the fund. Shibuwasa immediately wrote a letter to about 100 Japanese leaders with the aim of arousing their interest in the Armenian relief appeal. Contributions for the fund began to come from all classes of Japanese society—from ordinary people to government ministers, leading businessmen and royalty. A Japanese girl’s school assumed the full responsibility of two Armenian orphans. Prince Tokugawa Yoshihisa joined the relief campaign and sent a generous amount of money to the relief committee. He also took a leading part in supervising and distributing literature on the Armenian relief appeal to all members of the House of Peers.

Wirt continued his journey across the Pacific and successfully established relief committees in China, Korea, the Philippines, New Zealand, and Australia. Along with 15 other national committees, the Japanese committee became a member of the International Near East Relief Association headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland. It is not known how much money was collected by the Armenian Relief Committee of Japan during the life of the fund, or whether any Japanese nationals were mobilized to the sites of disaster. However, what we do know is that at all levels of Japanese society; practical sympathy was shown towards the plight of the Armenians, which resulted in the saving of many lives.

While Japan continues to be recognized today as a major international humanitarian force, a more thorough investigation into its philanthropic past reveals a deeper connection to international humanitarian relief than is widely known.

References

Peter Balakian, The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America’s Response, New York, HarperCollins, 2003.

James Barton, Story of Near East Relief: 1915-1930, New York, MacMillan & Co, 1930.

“Internal Affairs of Turkey 1910-1929,” General Records of the Department of State, Document no. 867.4016/117, Cable Record Group 59, U.S. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Loyal Lincoln Wirt, The World is My Parish, Los Angeles, Warren F. Lewis, 1951.

“The Near East in Japan,” The New Near East, Near East Relief, New York, April 1922, p. 12.

Charles V. Vickery, “International Golden Rule Sunday: A Handbook,” George H. Doran & Company, New York, 1926.

the material is taken from goo.gl/bKavba

Thanks to Anna Vardanyan for the provision of this material!