日本アルメニア友好:ソ連上の学校の授業から始まったパーソナル·ストーリー

June 5, 2014

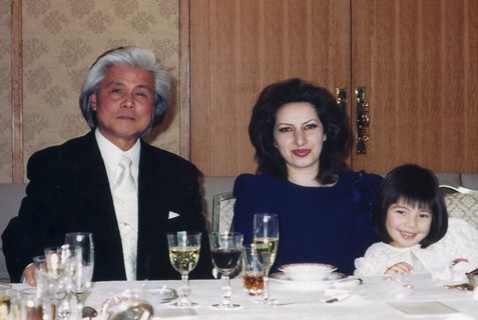

Photo: Hideharu Nakajima, his wife Melanya, and their daughter Anahit

Hideharu Nakajima has been to Armenia many times, most recently to participate in a meeting of regional representatives tasked with coordinating events to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide.

However, his familiarity with Armenian culture and history dates back to the 1950s when in Japan, as a junior high school student, his class was studying the Soviet Union.

“I was placed in a group given the Caucasus,” he tells Hetq. “We studied the language, dress and culture of the region. That’s when I understood that Armenia had a very ancient culture.”

The young Nakajima was particularly interested in the Armenian alphabet. He says that at the time he knew nothing of the Armenian Genocide and was puzzled why the once large country of Armenia became so small.

The students used an encyclopedia called Tamagava, which each school had for their studies about the Soviet Union. They also had a geographical dictionary at their disposal. But that was their extent of his knowledge of Armenia. He learnt more when he studied the Roman Empire at high school.

“The name of Armenia kept cropping up especially linked with the Persian invasions. I found out that Mesopotamia and Armenia had huge empires at the time.”

Based on his scanty knowledge, Nakajima believed that Armenia was located in an area that was difficult to traverse due to climatic and other features. This opinion was especially formed on the basis of the complaints raised by the soldiers under the command of Lucius Licinius Lucullus, a politician of the late Roman Republic. The soldiers complained about the mountainous terrain and the sudden snow storms that hampered their military advances.

“I realized that I would have to visit Armenia one day.That day arrived in 1980 on a working trip to Rome with my director,” Nakajima says.

Nakajima, who has worked at a Japanese oil company ever since that time, says that the trip to Rome was via Moscow and that he asked his boss for the chance to visit Armenia on the return trip.

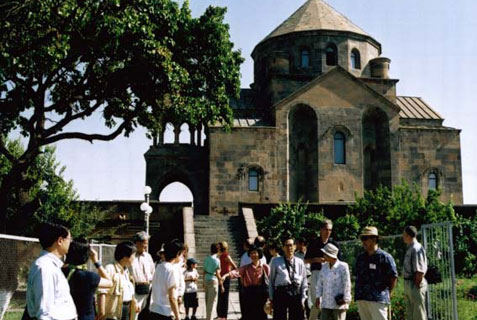

He spent two days in Armenia, visiting Etchmiatsin and being impressed with the architecture at St. Hripsimeh Church.

“The tufa stone is also used as architectural material in Japan. We have a green colored volcanic stone. I was particularly impressed by the changing hues of the buildings surrounding Lenin Square at different hours of the day due to the light. It was beautiful,” Nakajima says.

Nakajima tells me that he had read that Armenia was a land of rivers and mountains, both very important to the Japanese.

“My first visit spawned many thoughts about returning not only to Armenia, but the cities and towns of the Armenian Highlands, and to display it all back in Japan,” says Nakajima.

During his trips to western Armenia, Nakajima has visited Kars, Igdir, Bayazid, Van, Bitlis, Moush and Kharpert.

Visiting Armenia in 1987, the academician Melik Ohandjanyan suggested to Nakajima that he visit the Sardarabat memorial complex. It was there that he first met Melanya Baghdasaryan, one of the tour guides who knew English, and who was to become his future wife.

“At the time I was studying the Russian Revolution, and by extension, Armenia. Melanya assisted me. We corresponded by mail and she sent me important material,” Nakajima says.

During a 1991 trip to Armenia Nakajima made a marriage proposal and the couple were wed the following year. Standing in as godfather was Melik Ohandjanyan.

While Nakajima has never learnt Armenian, his wife has learnt Japanese, thus bridging the language gap.

The couple has one daughter, Anahit. The girl, now twenty, speaks Armenian poorly. She quickly forgets what she learns on her visits to Armenia because the family speaks Japanese at home and there are so few Armenians in their home town of Tokyo.

According to the Armenian Embassy in Japan, there are only fifty Armenians in the country, of which fifteen reside in Tokyo.

“Perhaps the reason is because Japan was a closed country until the end of the 19th century and it only had one open port of call,” says Nakajima.

The Japan-Armenian Friendship Association was created in 1991. It publishes two quarterly magazines in Japanese called Araks and Ararat.

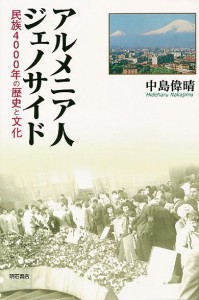

Nakajima has authored three books on Armenia.

“Due to the work of our group, the number of Japanese interested in Armenia and the Armenian culture has grown. Before the establishment of the Armenian Embassy in Japan, we were the only link between the two countries,” he says.

Nakajima now serves as the head of the regional committee gearing up for the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide and works closely with the Ministry of Diaspora Affairs in Armenia.

A work entitled “Book of Facts” is scheduled to be published in Japan in 2015. It is based on the writings of U.S. Ambassador Henry Morgenthau and Wolfgang Gust’s book “The Armenian Genocide”.

Films will be shown at the memorial events in Japan. There will also be a talk about Diana Abgar, who served as the Ambassador of the First Armenian Republic to Japan.

the material is taken from http://hetq.am/eng/news/54987/japanese-armenian-friendship-a-personal-story-that-began-with-a-school-lesson-on-the-soviet-union.html#.U5BjBBs5tOk.facebook